The ancient stadium of Dion is an earthen structure. It is located in the area of the sanctuaries, south of the city wall and northeast of the Hellenistic theatre. The dating of the stadium is based on a large number of coins found during the excavation. They represent almost all the Macedonian kings, from Alexander I (498-454 BC) to Philip V (238-179 BC). The earliest coin is a silver tetrobol (with a horse on one side and a helmet on the other) of Alexander I, whose coins continued to circulate for many years after his death. However, it is a serious possibility that this coin, taken together with the issues discussed below, may date the construction of the stadium many years before the time of Archelaus, who was probably simply the reformer of the Olympia at Dion.

The stadium of Dion is connected to the “Olympia at Dion” mentioned in ancient sources. These games are also attested by an inscription of the late 4th century BC,now on display in the Archaeological Museum of Dion. The inscription, which was originally set up in the sanctuary of Olympian Zeus, refers to gymnic (athletic) and scenic (theatrical) games, which were presumably held in the stadium and theatre of ancient Dion, the sacred city of the Macedonians, which may without exaggeration be called the Olympia or Delphi of the North. The excavation data show that the stadium of Dion retained its original plain, earthen form until Roman times, whereas the theatre was radically renovated in the 3rd c. BC, with the widening of the cavea and the erection of a majestic stage building with amarble proscenium. Both monuments are obviously directly connected to cult, as we can see both from their close relationship to the sanctuaries outside the city walls and from the references in ancient sources to the “Olympia at Dion”.

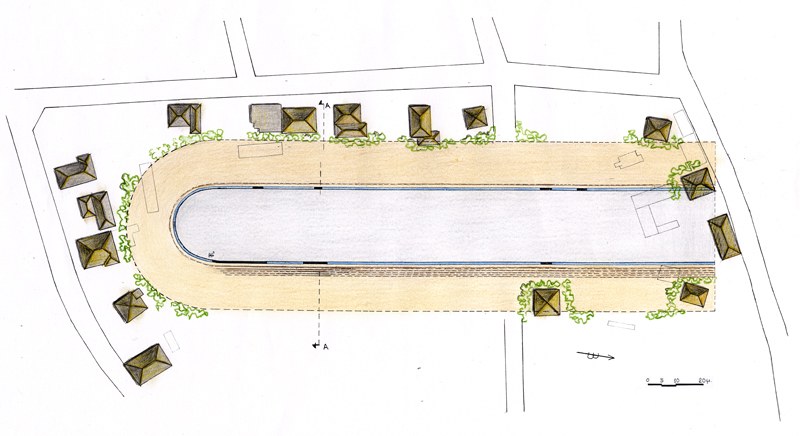

The excavation of the monument has not yet been completed, so our knowledge of both its form and structures is fragmentary. The stadium of Dion was built outside thecity walls, in direct relationship with the sanctuaries and theatre, on a slight incline, with almost exclusively earthen structures. The ground had to be excavated to form the west slope and banked up to form the east slope. The seating steps were simply dug into the slopes, as was the perimetric drainage channel. At its south end the stadium formed a semicircular sphendone, while the west end, where the entrance must have been, is now lost under modern buildings and the tarmac village road, so the total length of the stadium is currently unknown. The stadium retained its original earthen form throughout its long history, until it fellinto disuse in the Roman era. Despite its plain construction and humble materials, it was, overall, a monumental and also completely functional structure, imposing due to both its size and its perfect integration into its surroundings, forming as it did a simple landscaping of the natural terrain. The stadium and the Hellenistic theatre with their earthen masses, and the city wall with its ditch, embraced the area of the sanctuaries and protected them from the rainwater rushing down the slopes of Mt Olympus.

Giorgos Karadedos Associate Professor, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki

Ancient Stadium of Dion

Stadium

Photographic documentation and drawings of the excavation trenches are held in the archives of the Dion University Excavation

Archaeological site of Dion (in the area of the sanctuaries, south of the city wall and northeast of the Hellenistic theatre), Dion-Olympos Municipality, Pieria Prefecture (figs. 2, 3).

The dating of the stadium of Dion is based on a large number of coins found during the excavation. They are collectively important, since the area of the stadium with its high slopes was quite isolated, meaning that the coins could not have been transported there by rainwater flowing from elsewhere.The coins represent almost all the Macedonian kings, from Alexander I (498-454 BC)to Philip V (238-179 BC). The earliest coin is a silver tetrobol (with a horse on one side and a helmet on the other) of Alexander I, whose coins continued to circulate for many years after his death (fig. 13a). However, it is a serious possibility that this coin, taken together with the issues discussed below, may date the construction of the stadium many years before the time of Archelaus, who was probably simply the reformer of the Olympia at Dion. The stadium of Dion is connected to the “Olympia at Dion” mentioned in ancient sources. These games are also attested by an inscription of the late 4th century BC,now on display in the Archaeological Museum of Dion. The inscription, which was originally set up in the sanctuary of Olympian Zeus, refers to gymnic (athletic) and scenic (theatrical) games, which were presumably held in the stadium and theatre of ancient Dion, the sacred city of the Macedonians, which may without exaggeration becalled the Olympia or Delphi of the North. The excavation data show that the stadium of Dion retained its original plain, earthenform until Roman times, whereas the theatre was radically renovated in the 3rd c. BC,with widening of the cavea and the erection of a majestic stage building with a marble proscenium. Both monuments are obviously directly connected to cult, as we can see both from their close relationship to the sanctuaries outside the city walls (figs. 2, 3) and from the references in ancient sources to the “Olympia at Dion”. It is characteristic of the sanctuaries of Dion that the Pierian Muses – born, according to legend, in the foothills of Mt Olympus – enjoyed almost equal worship with Zeus. It is therefore only to be expected that artistic as well as gymnic contests were held at Dion. The same is true of Delphi, where the Pythian Games were originally musical contests, to which athletic contests, held every four years, were only added after 582 BC, during improvements to the Games. According to Diodorus, Archelaus (413-399 BC) “first held”, in honour of Zeus and the Muses, “scenic contests” and a “festival” lasting nine days, one for each Muse. After Archelaus, the sources indicate that other Macedonian kings also played an important part in the celebration of the “Olympia at Dion”, providing financial support, inviting major figures and presenting prizes. In the summer of 348 BC,following the destruction of Olynthos, Philip II went to Dion and awarded honours by giving wreaths to the victors at the Olympia there. 4

The question of when the Olympia at Dion were established is difficult to answer with the information currently at our disposal. At Dio, as at other sanctuaries (Delphi,Olympia), the artistic and gymnic contests very probably long predated Archelaus, who probably reformed and elevated an existing institution. It seems unlikely that a place where the Muses were worshiped would not have hosted splendid sacrifices, luxurious banquets and contests before Archelaus’ time, in a manner similar to that of the corresponding festivities at the Pythian, Nemaean and Isthmian Games of Southern Greece. In any case, the stadium of Dion itself probably predates Archelaus, as the coins found within it indicate.Nor do we know when gymnic contests ceased to be held at the stadium of Dionended. Several Roman coins were discovered during its excavation. We also know that Lucian, who visited Macedonia, chose to present his work at the Olympia at Dion, appearing in public and declaiming his speech “Herodotus or Aetion” in the stadium of Dion, which, as he remarked, was nowise inferior to that of Olympia.

The excavation of the monument has not yet been completed (see Excavation-Interventions), so our knowledge of both its form and structures is fragmentary (fig.4). The excavation began in July 1995. From the second day, after the removal of the cultivated topsoil and under a thin layer of dark, brownish-red, gravelly earth, the floor of the conistra (track) began to appear. It is made of clear, yellowish-red beaten earth (fig. 5a). Over this original floor, which dates from the construction of the stadium, a second floor 8-10 cm deep has formed over time. This consists of dark earth containing tiny shattered sherds and carbonised organic material, either grass or sweepings. This second layer is linked to the use of the stadium until its abandonment and was formed gradually, as fresh earth was added to the conistra each year before the opening of the gymnic contests. This floor is intersected by a trench dug into the ground, approximately 60 cm wide and 30-40 cm deep (figs. 5a, 7, 8). This is the drainage channel running round the stadium (fig. 4), which, like the stadium itself,slopes slightly south to north to allow rainwater to flow off into the adjacent ditch of the wall (fig. 2). Along the west side of the drainage channel runs a perimetric passage way about a metre wide, above which earthen steps begin to be formed on the slope, with an average width of 65-70 cm and height of 12-15 cm (figs. 5a, 8). Only 10 steps have been uncovered upwards, but there were certainly many more. From the 10th step up, the original height of the slope has been lost. In this digging, as in theadjacent ones excavated over the next few days, there were no indications of permanent built structures either in the track and drainage channel or on the seating steps. Similar low, exclusively earthen arrangements have also been found at other stadia, such as that of Elis. The trench was extended east, where the continuation of the track floor and the drainage channel on the east side of the stadium were found (fig. 4). This gave us the width of the stadium, about 27-27.5 m. Another three diggings were opened north and south of the first, providing excavation data on the continuation of the stadium, the drainage channel and the earthen steps. 5

New trenches were dug south of the modern road that intersects the stadium at right angles (fig. 4). In these diggings, too, exactly the same structures were noted: the track with its completely flat earth floor, sloping slightly south to north, the perimetric drainage channel (fig. 10) for conducting rainwater towards the ditch of the wall, and the earthen steps on the east and west slope. In the diggings on the east slope werefound fragments of thick bricks similar to those used to construct the seating steps of the theatre of Dion, in both its Classical and its Hellenistic phase. It is very likely that a small part of the stadium may have had brick seats forming a platform for the members of the judges’ committee or officials, as in the stadium of Olympia. However, as no bricks have been found in situ, this remains simple conjecture. Excavation in this part of the stadium brought an older digging to light (fig. 4). As the excavation in this trench had proceeded to a great depth in 1973, it provided an opportunity, without necessitating the destruction of new parts of the earthen steps, to identify the ancient natural ground level and estimate the depth of the fill needed to construct the east slope (fig. 5b). In the southernmost digging, the drainage channel and steps curve southwest, delimiting the beginning of the semicircular sphendone of the stadium (figs. 4, 6). The excavation could not continue further south to reveal the whole sphendone due to the presence of fenced vegetable gardens. In this digging, very close to the curved part of the drainage channel, an ashlar measuring 1.14×0.80 m was discovered in situ, set into the earth and only just projecting from the earthen track floor (figs. 6, 11). This ashlar has a large, square mortice in its upper surface, 6 cm deep, containing several fragments of white marble with well-worked flat surfaces and corners. This indicates that the ashlar forms the base of a marble pillar, square in section. Despite the limited extent of the excavation, the selection of the digging sites and the systematic and particularly careful excavation has permitted us to draw valuable conclusions and gain a general idea of the shape of the stadium (fig. 12). The stadium of Dion was built outside the city walls, in direct relationship with the sanctuaries and theatre (figs. 2, 3), on a slight incline, with almost exclusively earthen structures. The ground had to be excavated to form the west slope and banked up to form the east slope (fig. 5b). The seating steps were simply dug into the slopes, as was the perimetric drainage channel.

At its south end the stadium formed a semicircular sphendone, while the west end, where the entrance must have been, is now lost under modern buildings and the tarmac village road, so the total length of the stadium is currently unknown. The stadium retained its original earthen form throughout its long history, until it fell into disuse in the Roman era. Despite its plain construction and humble materials, it was, overall, a monumental and also completely functional structure, imposing due to both its size and its perfect integration into its surroundings, forming as it did a simple landscaping of the natural terrain. The stadium and the Hellenistic theatre with their earthen masses, and the city wall with its ditch, embraced the area of the sanctuaries (figs. 2, 3) and protected them from the rainwater rushing down the slopes of Mt Olympus.

Only a very small part of the monument has been revealed, in separate sections; this being an exploratory excavation, the trenches were dug at various points to allow as many conclusions as possible to be drawn. The whole of the monument lies on non-expropriated property, and some modern buildings have also been constructed, mainly on the west slope of the stadium. Despite the unfavourable circumstances, the monument could be revealed to asatisfactory degree and promoted, on condition that the expropriations go forward, the modern road cutting it in two is abolished, building on the site of the stadium is frozen and some of the modern buildings are demolished, though only a few, to avoid provoking social upheaval in the village (fig. 12)

The site of the ancient stadium of Dion was first identified by the British officer W.M.Leake, who visited the area in December 1806. From observations of the terrain, he located first the stadium, the theatre and the foundations of a large building, and immediately afterwards the ruins of the Dion city walls.These discoveries were repeated half a century later by L. Heuzey, and then in 1928-1931, with the beginning of the first excavations at Dion by G. Sotiriades, who noted the site and shape of the theatre and stadium quite accurately on a “contour diagram”(fig. 1), prepared by the Hellenic Military Geographical Service and published by the excavator himself. Despite the clear determination of the site of the stadium, Sotiriades only ensured that the area within the walls was excluded from allocation to farmers and protected as an archaeological site, leaving the stadium and theatre unprotected. This led to houses and barns being built on the west slope of the stadium and the north part of the track, something which now poses serious problems to the monument. Sotiriades dug a few test trenches on the east slope of the stadium, without identifying structures or the track floor. In 1970 began the excavation of the theatre, whose earliest phase must have been a structure related to and contemporary with the stadium.

In 1993-1994 began the excavation of a large palaestra-like building, probably of the Hellenistic period, between the theatre and the stadium. During the same period, there was renewed interest in the stadium and a few test trenches were made; these, however, were dug by mechanical means and did not provide substantial data on the exact location of the stadium. A systematic excavation was launched by G.Karadedos in July 1995, bringing valuable information to light and beginning the uncovering of this most important monument, one of particular significance to the history of gymnic games, the history of Dion and that of Macedonia as a whole. The excavation was particularly difficult because all the stadium structures were formed by simple landscaping of the terrain, making them very hard for even seasoned excavation workers to notice. Thus the weight of the excavation, not only at the level of supervision and documentation but also at that of manual work, was borne by the excavator.

The excavation of the stadium was limited to the two seasons of 1995 and 1996, due to the problems with properties that were never expropriated. Thus the monument was not revealed in full and the chance was lost to use it as a publically accessible monument and a place for low-impact events, games ceremonies or selected sports in the sacred city of the Macedonians as part of the 2004 Olympic Games in Greece. It is obvious that these will also be the permitted uses in future if the stadium is fully uncovered.

The property regime has prevented any use of the stadium to date, even as a publically accessible archaeological site, since the excavation trenches lie inside fenced plots of land.

–

–

–

–

–